Contra Dwarkesh on RL sample-efficiency via information theory

Dwarkesh Patel wrote an article RL is even more information inefficient than you thought. I’ve been trying to understand RL recently so I read the post with a lot of interest; but I think the main technical point in the post is wrong.

Without commenting on the broader point about RL sample-efficiency in general, in this post I claim that information-theoretic entropy of labels is not the right way to think about learning.

Dwarkesh’s post tries to compare “the amount of new information you can extract” in reinforcement learning vs supervised learning. For simplicity, he assumes the model is predicting a single token. The two settings are:

Supervised learning: we update on the correct token

RL: the model predicts a token, and gets a binary outcome (correct or not).

Dwarkesh’s claim is that the information gained in these two settings depends strongly on the pass rate p, which is the probability of getting the correct token.

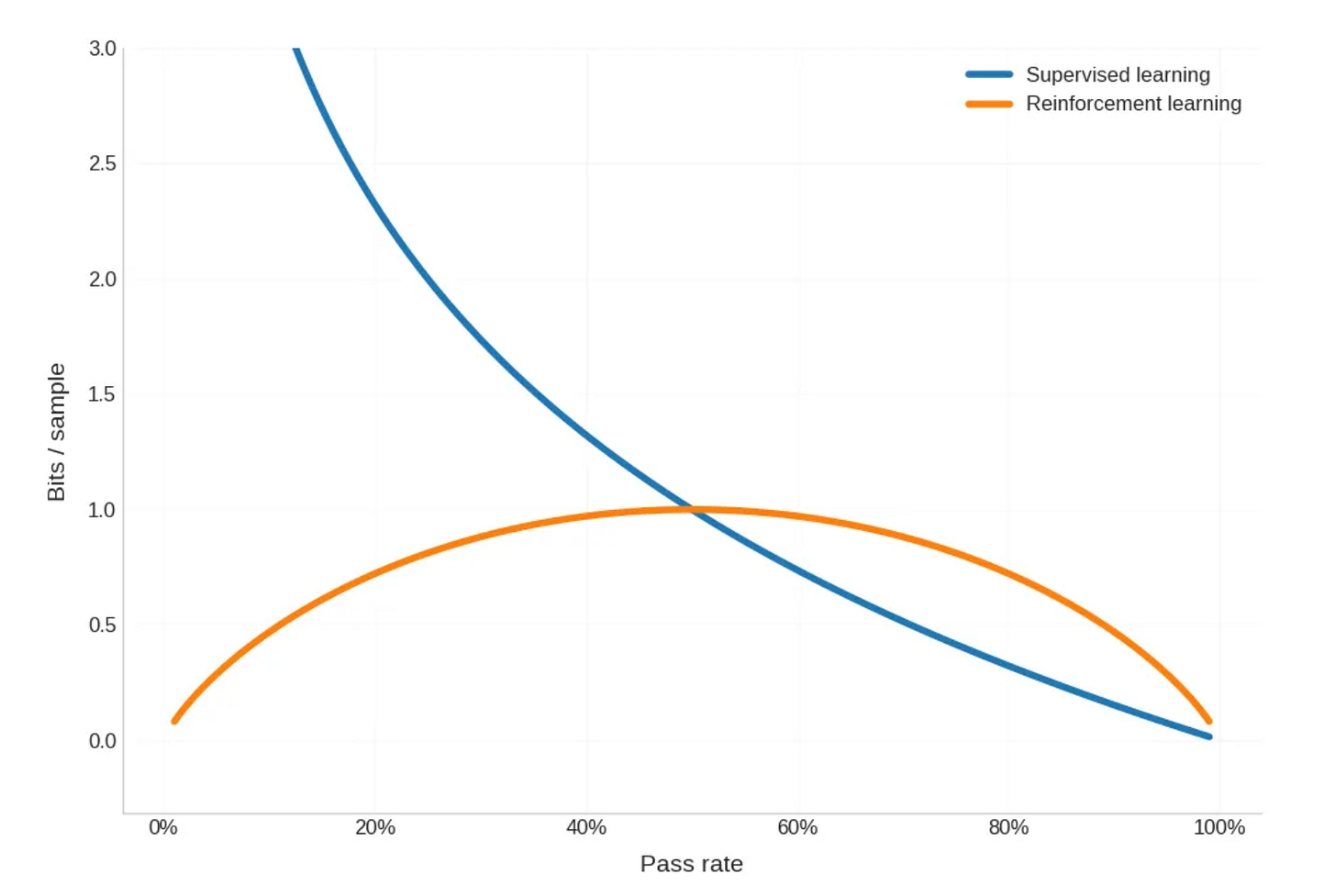

Concretely, Dwarkesh computes the information gain as -log(p) for supervised learning and H(p) = -p log(p) - (1-p) log(1-p) for RL.

From the plot we can see that the claim is as follows:

When p < 0.5, we can learn more information from supervised learning than from RL.

When p > 0.5, we can learn more information from RL than from supervised learning.

I think this is false. The correct statement is:

We can always learn more information from supervised learning than from RL.

This is because we always gain at least as much information from knowing the correct token as from knowing if our guess is correct. In other words, we can always turn supervised learning into RL by discarding information; but we cannot go the other way around.

We could formalize this via the data processing inequality, because the binary outcome is a function of the correct token given our prediction; but I don’t think it’s useful to do so here.

Instead, let’s produce the real plot comparing the information content of one sample (depending on whether we use supervised learning or RL) on a simple example.

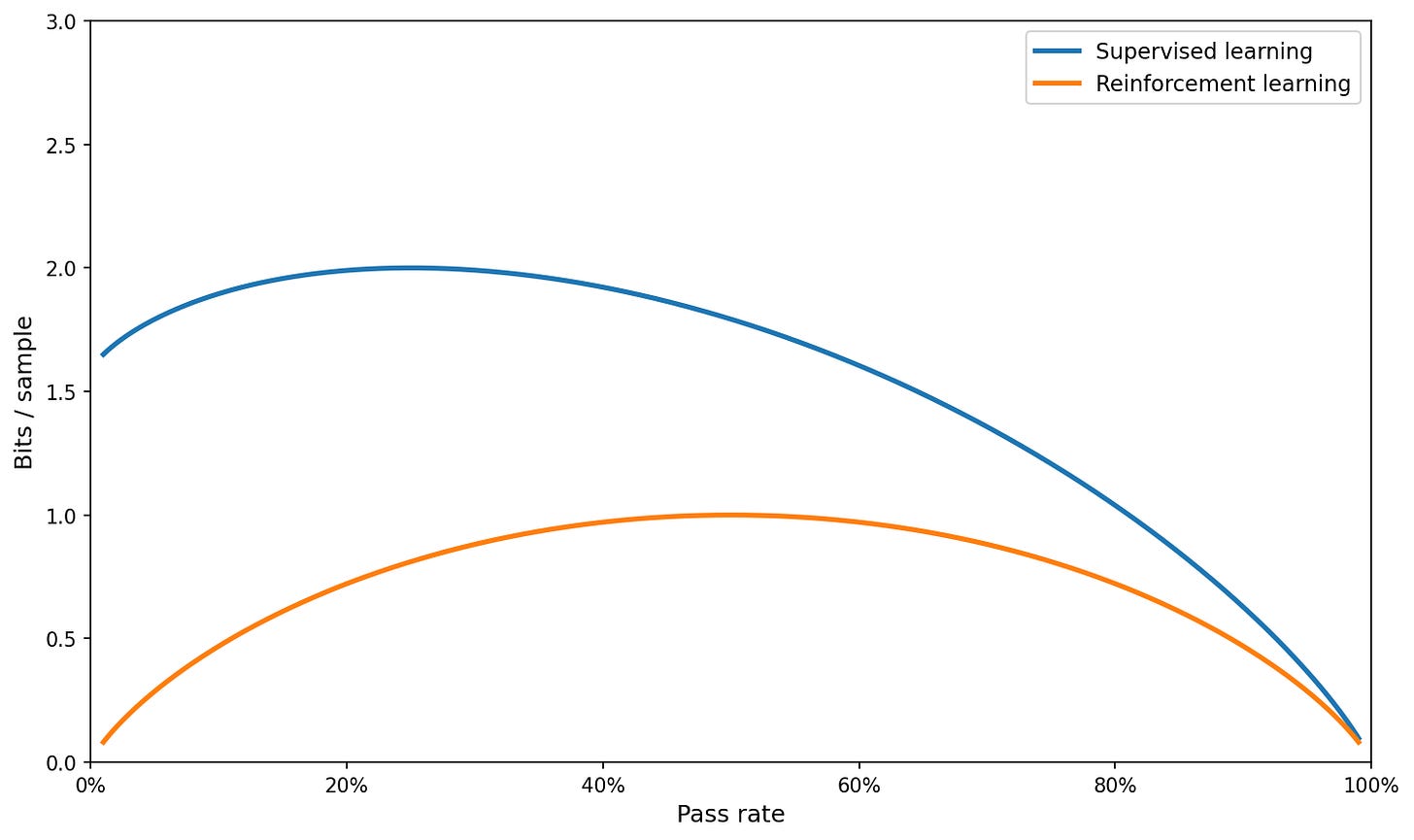

For the RL case, Dwarkesh’s post computes the entropy of the binary outcome assuming it is a Bernoulli trial with parameter p; this is H(p) = -p log(p) - (1-p) log(1-p). In the supervised learning setting, we know the probability of the correct token is p; but we have to assume the probabilities of the other tokens sum to 1-p.

One principled way to do so is to assume we are training on multiple-choice questions (with a,b,c,d options); so we will just set a uniform probability mass of (1-p)/K on K other tokens. The expected information content is then: -p log(p) - K (1-p)/K log((1-p)/K) = -p log(p) - (1-p) log((1-p)) + (1-p) log(K) and we can compute the plot as follows (for e.g. K = 3, as in the multiple-choice example):

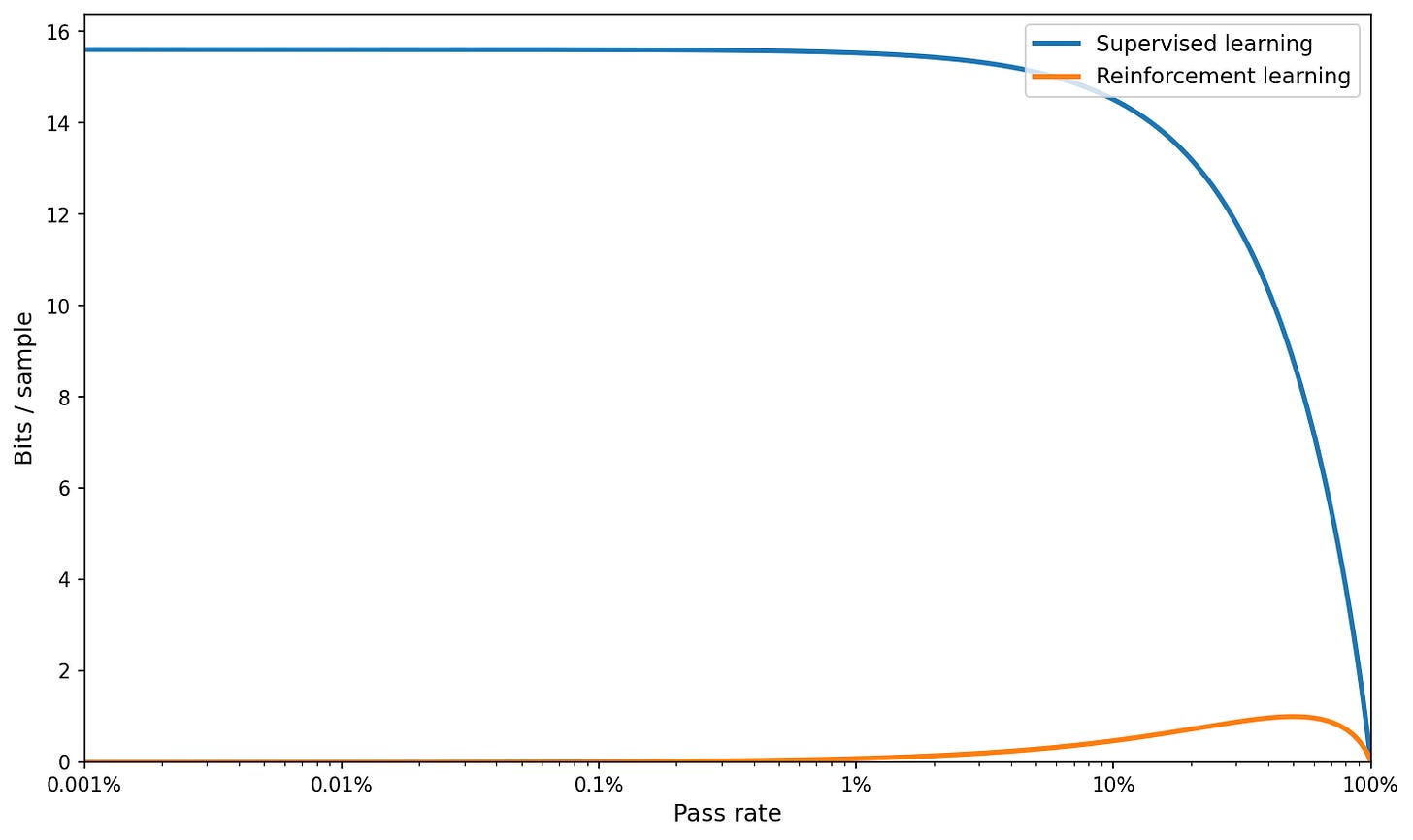

I think the rest of the section (with the log plot) does not really make sense after this; but let’s do it anyway, with a much larger K corresponding to the full vocabulary:

What is true is that RL is not useful at low pass rates, while supervised learning is. But we don’t need information theory to explain that; it’s just that RL with 0/1 rewards provides no feedback if you never get it correct.

What is the error in the original post?

The main issue is in computing information gain in supervised learning: assuming the expected information gain is -log(p) ignores the information gained from supervised learning when the model is wrong.

Think about it this way: if your model is predicting “Bob’s favorite animal is” → “cat” with 50% confidence when the correct token is “dog”, do these two approaches give the same amount of information?

You learn the correct token is not “cat”. We’ve effectively gained one bit of information: we know it’s not “cat”, but it could be any other animal.

You learn the correct token is “dog”. We resolved the entire uncertainty about Bob’s favorite animal.

It’s clear the second update is much more informative than the first.

Information content of labels is not a good intuition for learning

I think information-theoretical content of the labels gives a correct answer to the wrong question.

Consider again predicting a single token, but let us introduce a third commonly used learning setting

RL: the model predicts a token, and gets a binary outcome (correct or not).

supervised learning: we update on the correct token

knowledge distillation: we update on the logits produced by a teacher model

In RL, the information in the label is one bit. In supervised learning, the information in the label can be logarithmic in vocabulary size. But for distillation, the total amount of information communicated in a single label is linear in vocabulary size.

This means that a single update of soft distillation communicates more information than an entire training run of RL. Now, of course distillation is much more useful than RL; but not to the extent of “all of RL is not worth a single update of soft distillation”.

Nobody cares about the total information collected during training; we care about how good the downstream model is. And, the fraction of the information content of the signal that is useful for generalization can be very small, or very large. Any technical analysis of sample-efficiency of different learning methods must take this into account.

RL has something going for it here: it’s (1) on-policy; (2) the bits learned from RL directly correspond to performance on the task. For supervised learning, the tokens learned are off-distribution compared to what the model would sample at inference time, and the exact token choices have lots of useless information in them.

So, if we want to compute actual relative utility of different types of training per FLOP, this factor cannot be ignored. I believe accounting for all of this via back-of-the-envelope calculations is quite difficult, and extrapolating from empirical scaling results will yield better predictive models of reality.

Great post!

brilliant!! thanks for this great post!